The demands of being a lifeguard – swinging from inaction to life-and-death crises – are not for all. THEO PANAYIDES meets the president of the Limassol association, and finds a man always on the lookout

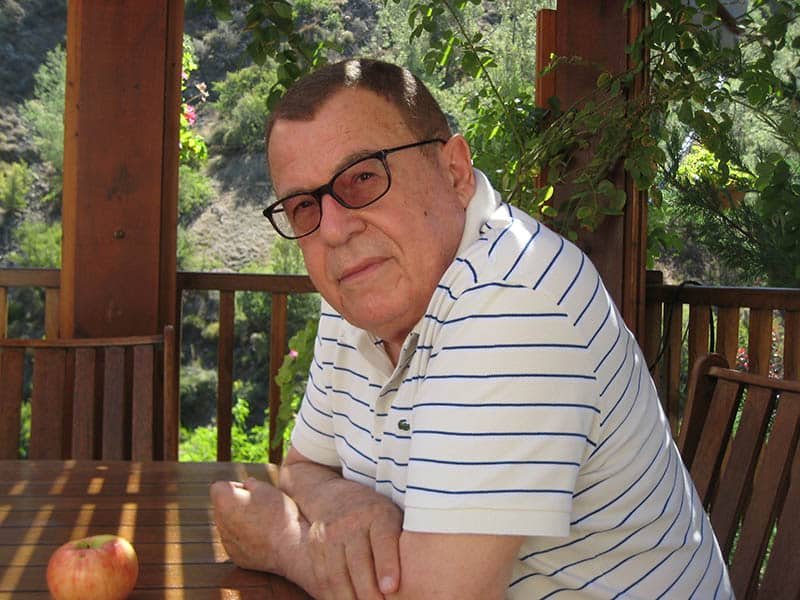

There’s an issue with the shades – or not an issue, but perhaps a question. Why won’t Avgoustinos Papadopoulos take off his sunglasses? It’s a kind of gesture, he tells me vaguely, preferring to keep them on not just for photos but throughout our interview. I think I understand, as we sit in the lifeguard’s tower overlooking the beach at the Four Seasons in Limassol; it’s a question of guarding his identity. You can have my knowledge, he tells me and every other interviewer, you can have what I know about being a lifeguard; I’ve been doing this for 25 years, I’m happy to share. But the eyes are the window to the soul, and you can’t have my soul.

Too dramatic? Maybe – then again, Avgoustinos is dramatic in his way, a restless almost-43-year-old with close-cropped hair and stubble, a scar on his back and a gold cross around his neck. He’s not relaxed. His legs keep twitching madly as he talks, like a bored little boy in the doctor’s office. He sips tea with lemon, intermittently picking out slices of lemon and eating them whole, spitting out the pips. “I’m a free spirit,” he tells me candidly. He takes out a packet of cigarettes and offers it politely; “D’you mind if I smoke?”. I shake my head, but tell him I’m a bit surprised that he smokes, given his profession. It’s true, he admits, but he doesn’t smoke much – and besides “it relaxes me. ’Cause I’m a bit hyperactive”.

His dad’s a musician, his mum a housewife; they met in Germany, where Dad was playing Greek music (Mum’s from Katerini in northern Greece). Avgoustinos, the eldest of three, was born in Munich but grew up in Cyprus, studied Hotel Management and tried the hospitality industry for a while, but couldn’t take it. “I’m a man of the sea,” he tells me. “I can’t do any other job”. He became a lifeguard in his teens – but it wasn’t a full-time job in those days, so he worked in bars and clubs as a doorman and bouncer. He quit a few years ago (and has barely been inside a club since), but for 19 years he was practically a fixture of Limassol nightlife. “People know me, and a lot of people know very well who I am,” he says, leaving me to wonder if there might be an edge to the second half of that sentence.

To be honest, this is not what I expected. The image of the lifeguard in popular culture (notably Baywatch) is calm, unruffled, imperious. The very concept of a lifeguard, high up on his perch looking out over the beach (we say ‘his’ though of course there are also female lifeguards, five of them in Limassol alone), suggests a superior being, serenely in control. Avgoustinos doesn’t seem especially serene – yet in fact his nervous energy is perfect for the job, for a simple reason which he emphasises again and again: “A drowning looks nothing like a drowning”.

Drownings in real life aren’t like in the movies. Watch what I’m doing, he urges at one point; I’m talking to you, but “my eyes are scanning everything” at the same time. (There are two small beaches, one on either side, and space for two lifeguards in the tower, though his partner sits outside while we talk.) A lifeguard should scan his territory every 30 seconds, he informs me gravely. A lifeguard can’t be smug, waiting to be called into action like Superman (or David Hasselhoff); in the vast majority of cases there won’t be any call, or indeed any sign whatsoever. “Most drownings take place completely silently,” explains Avgoustinos. “Without any splashing, without any cries, nothing. Because our breath is designed for breathing. Talking comes second. So, if you have someone who’s struggling to breathe – how’s he going to call out?”

Drowning people seldom cry out; even if they can, they’re often too embarrassed to call attention to themselves till it’s too late. Cries for help come from bystanders (assuming they realise that someone’s in trouble) or, in rare cases, from strong swimmers who feel unwell and have the presence of mind to call out. Feeling unwell is the first stage; the second is becoming gripped by stress – and the third is all-out panic, at which point the victim freezes up, the brain no longer gets properly oxygenated, movements become erratic and the person goes down in less than a minute. This is why a man of Avgoustinos’ restless disposition makes a good lifeguard – because you always have to be on the lookout, always scouring the water for signs of distress. “This job isn’t for everyone,” he says with a touch of annoyance, going on a rant against (some) lifeguards who are only there because politicians pulled strings on their behalf: “Just like everyone else in this country – the parties, you know what I mean…” Some fall to pieces when push comes to shove, unable to handle the sudden shift from days of inaction to life-and-death crisis.

Being a lifeguard is more of a proper job nowadays, hence the presence of unsuitable candidates who are only after a steady salary; an action plan was recently devised by the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre and the Ministry of the Interior (Avgoustinos, as president of the local lifeguards’ association, has fulsome praise for the heads of both those bodies), establishing year-round posts and hopefully extending the shift system to more towers. (At the moment, only five towers in Limassol – out of 24 – work with shifts, i.e. from 6am to 8pm.) More importantly, the medical equipment available to lifeguards has been hugely upgraded in recent years: stored in the tower around us are ‘Ambu bags’ for CPR, a portable defibrillator, a suction device to insert in a victim’s mouth and prevent choking, and so on. Indeed, Avgoustinos’ most memorable rescue wasn’t even of a swimmer, but a man who was sitting on the beach and suffered a heart attack – a rescue for which he was specially commended by the minister, the only lifeguard ever to have been so honoured.

He’s performed other rescues, of course: a wealthy Serbian gentleman, found desperately clinging to a buoy in the sea off the Hawaii Grand Hotel, who was so grateful he later plied Avgoustinos and his colleagues with whisky. (He also offered money but they refused, he says virtuously.) Or his very first professional rescue, as a boisterous teen on Malindi beach, which was actually surprisingly close to the Baywatch playbook: he’d gone down to the kiosk for a juice and a sandwich and, coming back, noticed a father and son whose little dinghy had capsized about 150m from land – so he simply plunged in without any rescue gear, forgetting the first rule of lifeguarding which is to avoid physical contact at all costs (a drowning person can pull you down with them), though of course “I was a very good swimmer, truth be told I was amazing at swimming”. He pulled the dinghy close to the father and kid, helped them grab hold, then pulled them out along with the boat. In 25 years, he may never have done anything more swashbuckling.

Then there are the others, those who slipped through his fingers. “See that guy there?” he says at one point, indicating a middle-aged tourist swimming alone. “The one who’s having difficulties? He’s almost treading water. If he was a little further in…” Prevention is everything, as already mentioned – but sometimes it happens too fast, even for experienced lifeguards; there’s only so much you can do, especially when a swimmer suffers a stroke or a heart attack. The sea isn’t always to blame.

Ah, the sea. Avgoustinos has a special relationship with the sea. Lifeguarding aside, he’s also a qualified Divemaster and fanatical spear-fishing enthusiast, freediving down to 25 or 30 metres. Don’t just call me a freediver, he cautions, “I’m a hunter” – and he hunts in the other way as well, with a gun up in the mountains, which he treats with the same quirky reverence as he does the sea. He hunts birds, but will always spare the hares (I assume it’s another gesture, like not taking off his sunglasses). He loves Nature in general, going for walks and picking mushrooms; he loves open spaces, and could never work in an office. Though he’s clearly very fit (he swims every day), I note that he doesn’t have the washboard stomach one associates with gym rats – which is no surprise, since he finds gyms claustrophobic and never goes to them. “I don’t like to be hemmed in.”

That applies metaphorically as well as literally – and indeed there’s something very pure (and a little immature) about this rugged, restless, unencumbered ‘man of the sea’, a free bird and happy commitment-phobe, a boy who never grew up. Is he married? Does he have any kids? He shakes his head: “I’m still raising little Avgoustinos,” he replies irresistibly. “I’m still the child. I don’t want any kids for the time being”. He loves women, but doesn’t know if he’ll ever be ready to settle down. Men and women are different, he muses: “I think a man has to be over 40 before he’s complete as a man. Especially in Cyprus, guys are so immature, never mind trying to start their own families… A woman is different. A woman has to find the right man to make things happen for her. We all know what a woman’s real job is.”

Having kids?

“Of course. After all, only a woman can give birth. That’s the true nature of a woman”. Avgoustinos is old-fashioned about things like that, nor does he agree with both parents working (though he admits it’s often necessary). “If you’re going to have kids so you can both work like dogs, don’t have kids, get a dog instead!” he quips.

He’s a throwback, in more ways than one – a happy Limassolian from the days when the city was smaller and cosier, before all the big money and tall buildings. “All of Limassol knows me, there’s no-one in Limassol who doesn’t know me!” he claims at one point – but that, I suspect, is no longer true. “We’ve sold out,” he admits sadly when I ask about the changes in the city. “We don’t own anything anymore… You’ll say to me, we’re just passing through anyway. OK. But that Cypriot culture is gone, that we used to have in the old days. In case you haven’t noticed, everything’s changed. People think about money, how to survive, there isn’t that…” He hesitates, unsure how to phrase it. “You know, the way we used to be in the old days.”

The old days were good to him, always the lord of his domain, whether he was guarding clubs or guarding beaches. He’s a bit embarrassed by his club years – he drank too much, and ate too much junk food – but it must’ve been a fun life, every night a party till the wee hours; there was seldom any trouble, after all “the troublemakers were my friends,” he says with a grin (everyone knew each other in the old Limassol). Has he ever thought about opening his own place – a bar, or something similar – with all his contacts? “Like I told you, big responsibilities aren’t for me,” replies Avgoustinos. When it’s your own business you’re there all the time, “and there’s no time left for living. I like to live free, do what I like, not have any working hours… All the energy that goes [into a business], what’s the point of it? Money? Like I said, we’re just passing through. I see people who grow old, they’re 100 years old and all they ever think about is money… I like to live free, my friend.”

Some may wonder how a man like this can handle the weight of being responsible for other people’s lives – but it’s not the same. Being a lifeguard is a different kind of burden. The energy it calls for is similar to that of the hunter in the mountains, or the bouncer at the door of the club: not a fixed routine but a constant tension, an alertness, a fearlessness, a readiness to deal with whatever should suddenly erupt. A more settled character might slacken, and lull himself into a false sense of security; Avgoustinos’ hyperactive style keeps him sharp.

‘Are you calm, or do you lose your temper?’ I ask at one point. “I’m impulsive!” he replies cheerfully. He’s calm, by and large, but liable to explode at any moment; like his job, he’s prone to upheavals. “I’m not slow, if that’s what you’re asking. I’m not slow. I’m very sparky, oh yes. I blow up, I catch fire, yes”. Right at the end, as a special favour, he takes off his shades, just for a moment or two, then smiles and goes back to scanning the sea for swimmers in peril. I say goodbye – but, before heading back to Nicosia, change my clothes in the car and go for a quick swim in the beautiful, warm August surf. Seems rude not to.

The post Leading lifeguard is a man of the sea appeared first on Cyprus Mail.

How will such an active, dynamic man cope with working alongside civil servants (not to mention the mukhtars of small mountain villages) on the Troodos plan? It’s a valid question. Yiannakis is private-sector through and through, and scathing when it comes to government departments: “They sit there, they take no initiative, they only do what their bosses instruct them to do… They discover that it’s easier to remain apathetic; the salary’s coming anyway”. A big part of transforming Kalopanayiotis was chasing EU funds to allow the villagers to restore their old homes (not to make them look new, he clarifies, just to give them “the look they used to have”; roof tiles in place of corrugated iron, that kind of thing) – yet he had to employ someone full-time just to run the weekly gauntlet from department to department, or the applications would never have been processed in time. Once, he recalls, he took the initiative to make a development plan for Marathasa, expecting the relevant minister to welcome his ideas; instead, the man raged at him for acting without permission, “and he shouted at every employee who’d helped us. So yes, there is a very big institutional problem”.

How will such an active, dynamic man cope with working alongside civil servants (not to mention the mukhtars of small mountain villages) on the Troodos plan? It’s a valid question. Yiannakis is private-sector through and through, and scathing when it comes to government departments: “They sit there, they take no initiative, they only do what their bosses instruct them to do… They discover that it’s easier to remain apathetic; the salary’s coming anyway”. A big part of transforming Kalopanayiotis was chasing EU funds to allow the villagers to restore their old homes (not to make them look new, he clarifies, just to give them “the look they used to have”; roof tiles in place of corrugated iron, that kind of thing) – yet he had to employ someone full-time just to run the weekly gauntlet from department to department, or the applications would never have been processed in time. Once, he recalls, he took the initiative to make a development plan for Marathasa, expecting the relevant minister to welcome his ideas; instead, the man raged at him for acting without permission, “and he shouted at every employee who’d helped us. So yes, there is a very big institutional problem”.

I don’t often talk to the under-30s, but Marianna seems a plausible poster child: so focused, so grounded – a child of crisis and recession – yet also serious when it comes to self-fulfilment. The difference between her generation and previous ones, she claims, “is that your job needs to be something you really like. It’s not like you’d work just for money… People aren’t afraid to go back to studies, even at 28”.

I don’t often talk to the under-30s, but Marianna seems a plausible poster child: so focused, so grounded – a child of crisis and recession – yet also serious when it comes to self-fulfilment. The difference between her generation and previous ones, she claims, “is that your job needs to be something you really like. It’s not like you’d work just for money… People aren’t afraid to go back to studies, even at 28”.

One couple wanted a donkey so she had one brought down from a donkey farm, garlanded with flowers for the big day. Another bride – staying with the equine theme – asked to ride to church on a horse, like an Amazon, to be met by her groom at the entrance and coaxed off her mount with a bouquet of flowers. Alas, the horse got skittish and refused to play along, necessitating a delay while Lily and Rena tried to find a replacement horse – which of course had its own problems, since the bride had taken riding lessons on that particular horse and felt a bit insecure on some random steed. (Being thrown off a horse on your wedding day would indeed be memorable.) Things go wrong occasionally; just last week, the groom fainted dead away in the middle of the ceremony (was it the heat? stress? who knows) and the priest had to resume with the couple sitting down. Then there was another groom who got cold feet, and wouldn’t get in the car to go to church – though she also recalls the “cool brides”, like the woman whose heel broke just as she was leaving the house. “She just tossed it, put on another pair of shoes, and we carried on.”

One couple wanted a donkey so she had one brought down from a donkey farm, garlanded with flowers for the big day. Another bride – staying with the equine theme – asked to ride to church on a horse, like an Amazon, to be met by her groom at the entrance and coaxed off her mount with a bouquet of flowers. Alas, the horse got skittish and refused to play along, necessitating a delay while Lily and Rena tried to find a replacement horse – which of course had its own problems, since the bride had taken riding lessons on that particular horse and felt a bit insecure on some random steed. (Being thrown off a horse on your wedding day would indeed be memorable.) Things go wrong occasionally; just last week, the groom fainted dead away in the middle of the ceremony (was it the heat? stress? who knows) and the priest had to resume with the couple sitting down. Then there was another groom who got cold feet, and wouldn’t get in the car to go to church – though she also recalls the “cool brides”, like the woman whose heel broke just as she was leaving the house. “She just tossed it, put on another pair of shoes, and we carried on.”

“When something is wrong it has to be put right. You have to try. I don’t attack the system as such. We still have a democracy and I don’t want to see it overthrown. I take on people within the system who make wrong decisions be it the president, ministers, whoever. If somebody is wrong, they have to be removed. It is usually people who do wrong – the actual law is good but implementation is wrong. Like the law on local government – something that is very close to me as a mukhtar.”

“When something is wrong it has to be put right. You have to try. I don’t attack the system as such. We still have a democracy and I don’t want to see it overthrown. I take on people within the system who make wrong decisions be it the president, ministers, whoever. If somebody is wrong, they have to be removed. It is usually people who do wrong – the actual law is good but implementation is wrong. Like the law on local government – something that is very close to me as a mukhtar.”

The second reason why there’s still a place for what she does, even in the age of Tinder (and Facebook, and the rest of the online landscape), is perhaps less obvious, having to do with Cyprus specifically – or not Cyprus per se, but any small country of a rather conservative bent. Simply put, Georgia is discreet, not to say anonymous. “All the ads are designed in such a way that the information is true, of course, but at the same time it’s also very vague, so no-one can identify who the person is,” she explains of the lonely-hearts capsules she keeps on file and places on her website (she also runs a daily listing in Politis newspaper). “It could be your brother – yet you wouldn’t know that it’s your brother.”

The second reason why there’s still a place for what she does, even in the age of Tinder (and Facebook, and the rest of the online landscape), is perhaps less obvious, having to do with Cyprus specifically – or not Cyprus per se, but any small country of a rather conservative bent. Simply put, Georgia is discreet, not to say anonymous. “All the ads are designed in such a way that the information is true, of course, but at the same time it’s also very vague, so no-one can identify who the person is,” she explains of the lonely-hearts capsules she keeps on file and places on her website (she also runs a daily listing in Politis newspaper). “It could be your brother – yet you wouldn’t know that it’s your brother.”

That’s a big issue, though, the increasing divide between elite and underclass. We do talk a bit about that, Rachel musing that democracy may fall by the wayside (“Will democracy look the same way it is? Will it fundamentally be a democracy?”) and the future, whatever it brings, may be less egalitarian than the present – which is already pretty unequal, especially in the US. “I think there are so many forces converging over the next two decades that make it a really ripe opportunity to re-think our economic structures, at the largest scale possible,” she says, decorously hinting that capitalism may no longer be fit for purpose. And what of universal basic income? What about those robots? Cyborgs? Cloned babies? What about all the old clichés, “flying cars, food in a pill”? So many futures, so little time.

That’s a big issue, though, the increasing divide between elite and underclass. We do talk a bit about that, Rachel musing that democracy may fall by the wayside (“Will democracy look the same way it is? Will it fundamentally be a democracy?”) and the future, whatever it brings, may be less egalitarian than the present – which is already pretty unequal, especially in the US. “I think there are so many forces converging over the next two decades that make it a really ripe opportunity to re-think our economic structures, at the largest scale possible,” she says, decorously hinting that capitalism may no longer be fit for purpose. And what of universal basic income? What about those robots? Cyborgs? Cloned babies? What about all the old clichés, “flying cars, food in a pill”? So many futures, so little time.

Fair enough; but the compulsion to go onstage and make light of life must’ve come from somewhere. It may well be reductive to say that Louis became a comic as a coping mechanism, especially since he didn’t start till his mid-20s – but perhaps telling jokes and facing life light-heartedly held a special significance for the young man, being the way his family had always coped with the pain in their midst.

Fair enough; but the compulsion to go onstage and make light of life must’ve come from somewhere. It may well be reductive to say that Louis became a comic as a coping mechanism, especially since he didn’t start till his mid-20s – but perhaps telling jokes and facing life light-heartedly held a special significance for the young man, being the way his family had always coped with the pain in their midst. It’s almost too good to be true, this amiable teddy-bear of a man who radiates unpretentiousness (conducting the interview in ‘plural’, i.e. formal Greek would be out of the question), claims to be unchanged by celebrity, and sets such store by people looking out for each other and dads spending time with their kids. Surely there’s a dark side somewhere, maybe a trace of the trauma he faced in his teens? Some may point to his unhealthy habits, all that smoking and over-eating. Some may even deplore his humour as primitive, sexist, ‘offensive’ – he adores Benny Hill, who would surely be “strung up from the London Eye” in today’s Britain; one YouTube clip has Louis showing the audience how a husband can check out a passing girl’s bum without his wife realising – but why should he care about such critics when his fans not only recognise him wherever he goes, but greet him as a friend? “People feel like I’m one of them,” he says happily.

It’s almost too good to be true, this amiable teddy-bear of a man who radiates unpretentiousness (conducting the interview in ‘plural’, i.e. formal Greek would be out of the question), claims to be unchanged by celebrity, and sets such store by people looking out for each other and dads spending time with their kids. Surely there’s a dark side somewhere, maybe a trace of the trauma he faced in his teens? Some may point to his unhealthy habits, all that smoking and over-eating. Some may even deplore his humour as primitive, sexist, ‘offensive’ – he adores Benny Hill, who would surely be “strung up from the London Eye” in today’s Britain; one YouTube clip has Louis showing the audience how a husband can check out a passing girl’s bum without his wife realising – but why should he care about such critics when his fans not only recognise him wherever he goes, but greet him as a friend? “People feel like I’m one of them,” he says happily.

Here, perhaps, is the biggest reason why Johnny Kevorkian succeeded where most people fail: he refuses to be ruled by self-doubt. “I just get on with it,” he tells me. “You kind of kick yourself and go ‘Stop feeling sorry. Just keep going. You know you can do it’. ’Cause, you know, there’s a lot of bad films getting made out there, and people are making them. You think ‘If they’re doing it, why can’t you?’. I think it’s all about being very resilient and bullish. I think that’s the key, really.”

Here, perhaps, is the biggest reason why Johnny Kevorkian succeeded where most people fail: he refuses to be ruled by self-doubt. “I just get on with it,” he tells me. “You kind of kick yourself and go ‘Stop feeling sorry. Just keep going. You know you can do it’. ’Cause, you know, there’s a lot of bad films getting made out there, and people are making them. You think ‘If they’re doing it, why can’t you?’. I think it’s all about being very resilient and bullish. I think that’s the key, really.”