With international renown, and patients, one Nicosia doctor offers contentious treatment to sufferers of Lyme disease and many other problems. Dismissing detractors as being in the pockets of Big Pharma, he tells THEO PANAYIDES of the importance of keeping up

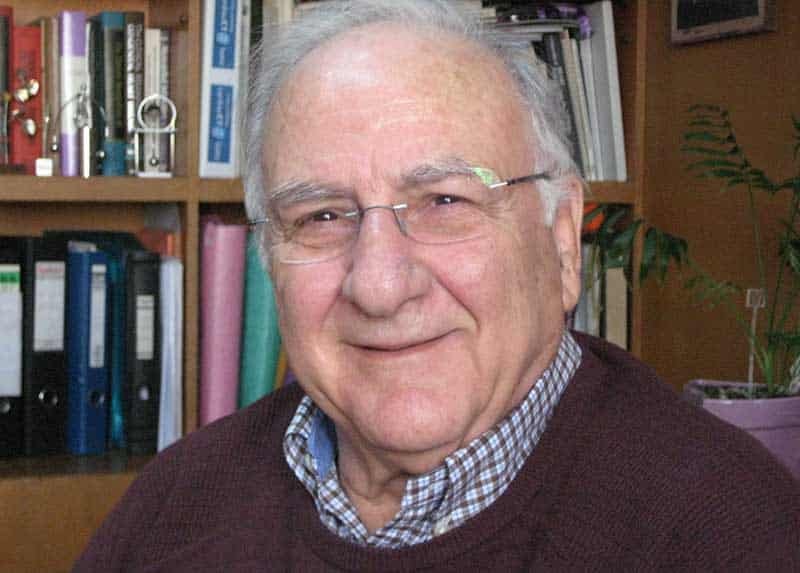

Dr Yuri Nikolenko looks like he must be a character, a plain-spoken, paunchy Ukrainian with a waddle in his walk and green eyes in a pale, pouchy face. The 59-year-old head of the Medinstitute Clinic in Nicosia has – or cultivates – a languid, affable manner, slowly manoeuvring his big bulk around the three floors of the clinic. “Give me one minute,” he calls apologetically, gazing across with a mournful bloodhound expression. “For the beautiful, it’s fourth floor,” he jokes faux-flirtatiously when a group of ladies in the lift seem unsure which button to press (they’re looking for Dermatology, run by Yuri’s daughter Valentina). He has a touch of the concierge or the bus driver, one of those professions that depend on being stolid and ingratiating – but in fact he’s a scientist and a chess master (a game he’s been playing since the age of four), a judo adept and former deep-sea diver; and he also runs this clinic which he founded in 1989, drawing patients from all over the world.

All that said, there’s an ethical dimension in publishing a profile of Yuri, indeed it’s not just ethical but also inescapable. We talk a lot about ozone therapy, sitting in his office at the Medinstitute – it’s a central part of what the clinic offers, albeit not the only thing – and anyone reading will presumably want to do some further research. Google ‘ozone therapy’, however, and the first thing that comes up – literally the first thing – is the Wikipedia article on the subject, which begins as follows:

“Ozone therapy is a form of alternative medicine that purports to increase the amount of oxygen in the body through the introduction of ozone. It is based on pseudoscience and is considered dangerous to health, with no verifiable benefits.”

Yuri seems unconcerned when I read the article out to him. “There are people [who] fight us, pharmaceutical companies,” he shrugs, his Greek still rather fractured after 30 years on the island. It may seem an inadequate response, given how unambiguous the article is (Wikipedia’s source, incidentally, is the Code of Federal Regulations of the US Food and Drug Administration) – but by that time I’ve already had a tour of the clinic, and heard enough to at least give me pause.

Yuri seems unconcerned when I read the article out to him. “There are people [who] fight us, pharmaceutical companies,” he shrugs, his Greek still rather fractured after 30 years on the island. It may seem an inadequate response, given how unambiguous the article is (Wikipedia’s source, incidentally, is the Code of Federal Regulations of the US Food and Drug Administration) – but by that time I’ve already had a tour of the clinic, and heard enough to at least give me pause.

The ozone-therapy room is down the corridor from his own office. I’m not sure exactly what the procedure involves – but he shows me a machine whereby ozone (a gas) is liquefied, after which the liquid ozone is introduced into the patient’s bloodstream. (Ozone is indeed dangerous to breathe, explains Yuri – it causes hyperoxygenation – but this liquefied form is quite safe, bypassing the lungs and going straight to the veins.) All three beds in the room are occupied, two of them by Helena and her son Adam who hail from Sweden by way of Britain. “I got bitten in Sweden in 2008, and Adam in 2010,” she explains – referring to Lyme disease, “an infectious disease caused by a bacteria named Borrelia spread by ticks” (Wikipedia again) which accounts for many of the overseas patients.

Lyme disease is increasingly in the news (pop star Avril Lavigne recently spoke of her battle against the illness, which is life-threatening) – yet healthcare systems in most places still haven’t caught up. In Australia, the disease isn’t even officially recognised; the Medinstitute gets around 500 patients from that country every year. In Sweden, according to Helena, a Dr Sandström was struck off for treating it, in contravention of official guidelines – which is partly why she and Adam have had to turn to “amazing people like Dr Yuri” in search of a cure. The third bed is taken by Patricia who’s come all the way from Wisconsin, having learned about the clinic through a Facebook page run by a former patient. She’s had Lyme for three and a half years; her friend Mary – also from Wisconsin – says she’s had it for 49 years, since the age of eight! Insurance won’t cover it in the US, and the treatment is “so expensive” there. They’re in Cyprus on a three-month visa, staying in an Airbnb and trying to heal their lives at the hands of this affable Ukrainian.

It’s all so perfect, I wonder for a moment if Yuri may have stage-managed these encounters (he is a chess master, after all) – but it’s not like he indicates who I should talk to. “You saw for yourself,” he notes. “I didn’t bring you the chosen ones.” Nor is it just Lyme disease. Jamal, from Dubai, has a condition where his liver and pancreas are unable to filter cholesterol; his cholesterol count is 5,000 (it should be under 200). He’s here getting his arteries cleaned, and – like the others – speaks warmly of the doctor. Also in the mix is a local lad, a 13-year-old boy suffering with a rare virus and howling piteously on a hospital bed – though his howls are apparently because he’s afraid to give blood (I see him later, looking considerably more cheerful). Yuri also tells me of other patients, one from Dubai who had stomach cancer (the tumor was 17cm in diameter), another – a Cypriot – who was stung by dozens of spiders which emerged from a nest in a hollow tree. We’ve even had our first local cases of Lyme, both in Paphos, though it’s unclear if they were bitten here.

Then there’s the Russian billionaire, a business partner of Roman Abramovich’s, whose once-shattered health has been restored by two years of therapy – and who apparently showed his gratitude by donating one of the expensive machines I see on my tour, possibly the ‘magnetoturbotron’ festooned with Cyrillic writing (it looks like an MRI, but is used for magnetic stimulation of the whole body) or the ‘barocamera’ for breathing problems and bronchitis. Dr Yuri is big on hardware, pointing out this or that bit of high-tech equipment as he waddles through the clinic. “I’ll send it to Herman at the factory, they can talk to Wikipedia,” is his final word on That Article, ‘the factory’ being the company in Germany which produces the ozone equipment. “We’re tired of fighting them,” he adds, speaking of the pharmaceutical companies. “They’re always putting something crazy”.

Is that it, then? Should we just dismiss the official line on ozone therapy as more crazy talk by Big Pharma (presumably in league with their cronies in the US government)? What to make of this miracle cure? On the one hand, meeting patients who’ve come halfway-round the world and truly believe they’re getting better doesn’t mean they are getting better. On the other, Yuri claims to have personal experience of the efficacy of his treatment – not just because he’s tried ozone on himself (it works as prevention as well as cure), but also because it saved the life of his wife Chrystalla.

When the clinic opened in 1989, soon after the couple arrived from Ukraine – they met in college, at the University of Kharkiv, and married soon after – it was much more conventional, with an emphasis on physical rehabilitation (that department still exists, run by their other daughter Nikoletta). Everything changed 23 years ago, when Chrystalla was struck down with severe neuropathy; doctors offered only a bleak prospect of slow deterioration and early death (all her fellow patients in the neurological ward have long since died, notes Yuri grimly) – so he did some research and found ozone therapy, which saved his wife as it’s saved many others. Fidel Castro’s doctors kept him alive for 17 years, through three types of cancer, using ozone, claims Yuri. The Germans discovered it first and used it during WWII, healing their wounded (and sending them back into battle) twice as fast as the Allies. “The greatest ozone therapist was Adolf Hitler!” he declares; I told you he was plain-spoken.

He’s also a character, that initial impression turning out to be accurate. He tears up a tissue to denote cancerous mutation, and extracts a string of worry beads from a desk drawer to illustrate what a virus looks like. He doesn’t have a doctor’s silky manners, coming off more as a rough-hewn savant or eccentric inventor – and indeed he’s an “accidental doctor”, having studied maths and physics (he was accepted to the prestigious Moscow Institute of Physics) before switching to medicine due to a mix-up with his papers. He’s good with his hands, hailing from a family of engineers. “I can build a house, I can do welding, anything”. One of his best friends in Cyprus (now deceased) was a simple shepherd named Socrates, a man who’d never finished primary school but could match his Athenian namesake for keenness of intellect: “If he’d gone to university, he’d have been a Nobel Prize winner!”. There’s no mention of friends who are doctors, or society types.

Patients, I assume, must be slightly nonplussed by this bulky figure with his quirky, un-medical phrasing: ozone has a third oxygen atom, he tells me (its chemical formula is O3, as opposed to O2) – but the third atom is “a boyfriend”, it can’t live with the other two. Employees, too (the clinic has a staff of about 20 people), won’t always agree with the way he does business. “I’m strict,” admits Yuri; the languid manner is just a façade, and he talks more than once of wanting things to be “like in the army”. (He himself had military training while at college – male students doubled as reservist officers in the Soviet Union – including brief experience of war zones in Africa.) All staff are tested on all new machines, and he’ll interview patients to get their feedback on nurses. Working hours at the Medinstitute are 8.30am to 8pm, with a two-and-a-half-hour break in the middle when (he says) almost everyone settles down for a power nap in a specially-designed environment. The nap is optional, he adds, then again you have to wonder.

Science is approached with the same systematic dedication. “I read 60 pages every day. Medical literature,” he tells me gravely. “I don’t read 59 pages. 60!” He’ll sit for hours if he finds something interesting, speed-reading pages in Russian or Greek then emailing questions to the authors. “Because science moves on,” he adds pointedly, thinking perhaps of his own situation. “Anyone who stands still and says ‘Oh, I don’t accept that’ – well, once upon a time people didn’t accept that the Earth was round”. New discoveries are made all the time – “then immediately killed by the pharmaceutical companies,” he adds grimly.

We should note that the Medinstitute Clinic isn’t entirely ‘alternative’, whatever that much-maligned word even means. It’s not that Yuri won’t prescribe antibiotics as needed; it’s just that ozone – he says – goes even further, and that’s not even mentioning the other wonders he claims to have on hand, like the brain stimulator (it produces endorphins) that’s ideal for minor troubles. “Let’s say you had a fight with your wife, you scratched your car, you spilled coffee on yourself, you got told off at work – so now your day is shit! OK?” he explains with his usual straightforwardness. That kind of hassle can get under your skin, you might be losing sleep and unable to shake yourself free, “the needle is stuck, like I say” – but then “you come to us, we put you under a machine, just 20 minutes,” raves Yuri, growing visibly excited: “Like the Terminator, chhhhhh, you get up – let’s go party!”

In the end, Yuri Nikolenko’s idiosyncratic style helps his cause, in a way that a standard bedside manner probably wouldn’t. It’s easy to believe – despite the bad publicity on Wikipedia – that there’s something more to medicine which this mad-scientist type might appreciate, and the greedy capitalists probably don’t. The weirdest tale he tells is of the North Korean doctoral student (and friend) who once saved his life in the USSR, when Yuri fell in a river after a parachute jump and developed pneumonia. His own hospital colleagues couldn’t help – but the North Korean did, by buying a black hen at market (!), cooking it for 12 hours with special mushrooms and herbs, and creating a kind of gelatinous broth which was “the greatest bio-stimulator I’ve seen in my life,” he marvels. “That’s why I say, ‘Never say never’. These people know things we don’t.” There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your pharmaceuticals.

Don’t some people call him a charlatan, though?

He shrugs, his bulk shifting and his eyes growing glassy, as if with boredom. “It’s their right,” says Yuri, the languid manner returning. “We have a licence to practice. I had about 30 Cypriots with me [at university], we all graduated together, so who can say that…?” He trails off, meaning ‘that I’m not properly qualified?’. “Let them take care of their own business. Let them work 16 hours like we do, and read up and so on, and maybe they’ll change their minds”. At the end of the day, he’s not too bothered – and not just because he seems to be doing well, earning plaudits from Russian oligarchs and ladies from Wisconsin alike. “There’s an old Arabic proverb,” opines Yuri mischievously: “‘The dogs bark, the caravan goes on’.” Let them bark; his mind is on bigger things.

The post Taking patients through the ozone layer appeared first on Cyprus Mail.

The smile is easy, the demeanour friendly – but there’s still a solid core to the inner person, something orderly and the opposite of sloppy. She’s focused, and perhaps a bit severe. Her husband tells a story about their first meeting, during her corporate stint after the BSc (it was at the same company where he still works now). “He calls me a snob,” she reports in mock-horror. “He says that nobody dared to speak to me, because I was so snobby-looking. Me?” gasps Jonilda indignantly. “I’m the sweetest girl in the world!” We laugh, of course – but you have to wonder (and she does wonder) if she might come off as a bit aloof without realising it. It ties in with something else, her memories of having faced discrimination at her Athens high school – though it wasn’t insults or violence, just a hurtful isolation. Was it perhaps a distance in herself which made others distant? What was she like as a person? “Sensitive,” she replies at once. “As dynamic as I was in my studies and career, I was sensitive in personal matters.” She smiles ruefully: “I’ve learned to camouflage it a little, but I still am”.

The smile is easy, the demeanour friendly – but there’s still a solid core to the inner person, something orderly and the opposite of sloppy. She’s focused, and perhaps a bit severe. Her husband tells a story about their first meeting, during her corporate stint after the BSc (it was at the same company where he still works now). “He calls me a snob,” she reports in mock-horror. “He says that nobody dared to speak to me, because I was so snobby-looking. Me?” gasps Jonilda indignantly. “I’m the sweetest girl in the world!” We laugh, of course – but you have to wonder (and she does wonder) if she might come off as a bit aloof without realising it. It ties in with something else, her memories of having faced discrimination at her Athens high school – though it wasn’t insults or violence, just a hurtful isolation. Was it perhaps a distance in herself which made others distant? What was she like as a person? “Sensitive,” she replies at once. “As dynamic as I was in my studies and career, I was sensitive in personal matters.” She smiles ruefully: “I’ve learned to camouflage it a little, but I still am”.

Though confined to a wheelchair for more than half her life, Toula has certainly not rested on her laurels. In the early years she helped the Radiomarathon Foundation (a non-governmental voluntary organisation) to raise money for children with disabilities and she was part of a citizen’s initiative for road safety, visiting schools and army camps and warning youngsters about the potential consequences of poor driving habits, including driving too fast. For the last ten years, she has been Vice President of the Organisation for Paraplegics in Cyprus (Opak) and still assists with road safety campaigns. “I now believe that when we go into high schools and the army it is probably too late. We should start in kindergardens and junior schools”.

Though confined to a wheelchair for more than half her life, Toula has certainly not rested on her laurels. In the early years she helped the Radiomarathon Foundation (a non-governmental voluntary organisation) to raise money for children with disabilities and she was part of a citizen’s initiative for road safety, visiting schools and army camps and warning youngsters about the potential consequences of poor driving habits, including driving too fast. For the last ten years, she has been Vice President of the Organisation for Paraplegics in Cyprus (Opak) and still assists with road safety campaigns. “I now believe that when we go into high schools and the army it is probably too late. We should start in kindergardens and junior schools”.

We shouldn’t oversell the idealism. For one thing, meeting his wife (also a doctor, in the state sector) was a big factor in deciding to stay. For another, it’s not like Lakis wasn’t making money in Cyprus too, as a US-trained cardiologist – and it wasn’t just the money, it was also a case of presiding over “a new era”, overseeing the transformation from public to private medicine. At the Centre, he and his colleagues introduced now-familiar tools like ultrasound examinations and exercise (a.k.a. stress) tests, importing the equipment themselves; on the island as a whole, a system was built up from scratch. “It was an exciting era, from the medical aspect. We had to do things for the first time in Cyprus. Organise seminars, invite foreign guests, foreign doctors”. He was president of the Cyprus Cardiology Society, liaising with colleagues from all over Europe. Medical associations were set up for various specialties – the same associations which are now lining up against Gesy.

We shouldn’t oversell the idealism. For one thing, meeting his wife (also a doctor, in the state sector) was a big factor in deciding to stay. For another, it’s not like Lakis wasn’t making money in Cyprus too, as a US-trained cardiologist – and it wasn’t just the money, it was also a case of presiding over “a new era”, overseeing the transformation from public to private medicine. At the Centre, he and his colleagues introduced now-familiar tools like ultrasound examinations and exercise (a.k.a. stress) tests, importing the equipment themselves; on the island as a whole, a system was built up from scratch. “It was an exciting era, from the medical aspect. We had to do things for the first time in Cyprus. Organise seminars, invite foreign guests, foreign doctors”. He was president of the Cyprus Cardiology Society, liaising with colleagues from all over Europe. Medical associations were set up for various specialties – the same associations which are now lining up against Gesy.

Doesn’t it create a distance, though? Doesn’t it make for a certain detachment in relationships, having had to harden oneself against life at an early age?

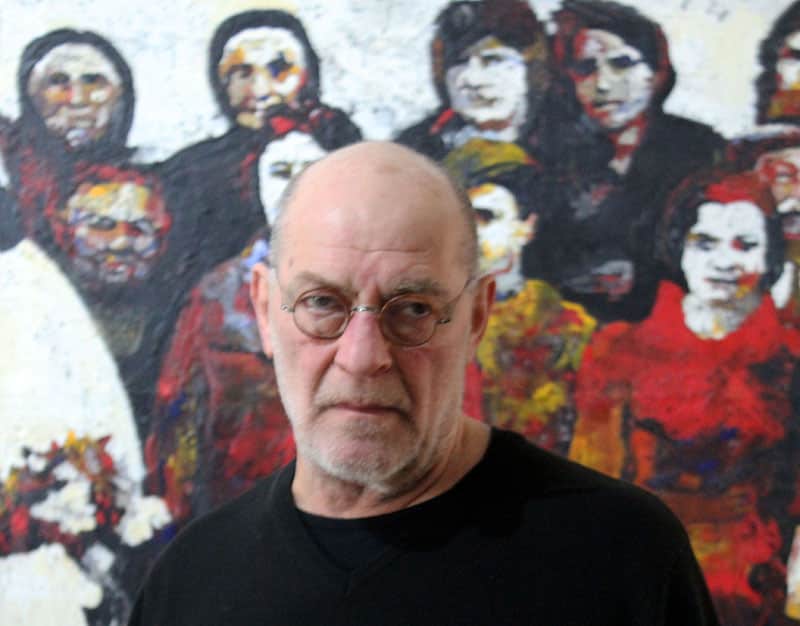

Doesn’t it create a distance, though? Doesn’t it make for a certain detachment in relationships, having had to harden oneself against life at an early age? Besides, his style of the past 20 years isn’t all he’s ever done, not by a long shot. He runs through a partial list: abstract art, installations, “arte povera using whatever I happened to find on the street, boilers nailed to the canvas and painted, entire radiators, body performance, painting kids from head to toe – then I wrapped them in a sheet, unwrapped them, and that was the print! – video art, with myself surrounded by glass and getting cut and so on…” He became known in his late 20s (having meanwhile come back to Cyprus, fought in 1974, returned to England and thence to France, where he found his first acclaim), but it wasn’t till his early 40s – his years in Athens – that he really became “indispensable to the society where I lived,” as he puts it, i.e. a leading light of the artistic community, no longer having to hustle for shows and stress about selling his work in the way of an up-and-coming artist.

Besides, his style of the past 20 years isn’t all he’s ever done, not by a long shot. He runs through a partial list: abstract art, installations, “arte povera using whatever I happened to find on the street, boilers nailed to the canvas and painted, entire radiators, body performance, painting kids from head to toe – then I wrapped them in a sheet, unwrapped them, and that was the print! – video art, with myself surrounded by glass and getting cut and so on…” He became known in his late 20s (having meanwhile come back to Cyprus, fought in 1974, returned to England and thence to France, where he found his first acclaim), but it wasn’t till his early 40s – his years in Athens – that he really became “indispensable to the society where I lived,” as he puts it, i.e. a leading light of the artistic community, no longer having to hustle for shows and stress about selling his work in the way of an up-and-coming artist.

I assume she means ‘home’ as in ‘home from the restaurant’ – but ‘home’ is actually Iceland, where she went to “ease my mind” and decide, after some thought, on a vegan/vegetarian place. It’s a poignant detail, the elusive sense of home for a person who’s been uprooted from her birthplace (though you’re never entirely uprooted; Inga tells me of a friend who lived in Sweden for 60 years, raised a family, then went back to Iceland alone to retire). It’s enough to unsettle a more anxious person – but Inga isn’t anxious, which may also explain why she’s managed to make a go of her mixed marriage. “I don’t panic easily,” she smiles. When she describes the Icelandic character as hard-working and “quite down-to-earth”, I suspect she’s thinking of herself.

I assume she means ‘home’ as in ‘home from the restaurant’ – but ‘home’ is actually Iceland, where she went to “ease my mind” and decide, after some thought, on a vegan/vegetarian place. It’s a poignant detail, the elusive sense of home for a person who’s been uprooted from her birthplace (though you’re never entirely uprooted; Inga tells me of a friend who lived in Sweden for 60 years, raised a family, then went back to Iceland alone to retire). It’s enough to unsettle a more anxious person – but Inga isn’t anxious, which may also explain why she’s managed to make a go of her mixed marriage. “I don’t panic easily,” she smiles. When she describes the Icelandic character as hard-working and “quite down-to-earth”, I suspect she’s thinking of herself.

Here, perhaps, is the missing piece of the puzzle – this organic, intuitive link he has to his creativity, whether as painter, composer or fashion designer. It’s the method of a person who creates not as a career, not as a structured process, but more as an extension (almost, you might say, a celebration) of himself – and another clue is surely contained in the title of his exhibition, because there’s a very important fact we haven’t yet mentioned about Yiorgos. It wasn’t just his talent of which he was unaware (or in denial?) for the first 20 years of his life. It was also his sexual orientation.

Here, perhaps, is the missing piece of the puzzle – this organic, intuitive link he has to his creativity, whether as painter, composer or fashion designer. It’s the method of a person who creates not as a career, not as a structured process, but more as an extension (almost, you might say, a celebration) of himself – and another clue is surely contained in the title of his exhibition, because there’s a very important fact we haven’t yet mentioned about Yiorgos. It wasn’t just his talent of which he was unaware (or in denial?) for the first 20 years of his life. It was also his sexual orientation.

“Are you a happy person?” I ask at one point. “Are you an optimist?”

“Are you a happy person?” I ask at one point. “Are you an optimist?”

He and Simpson (now perhaps the best-known BBC reporter) filmed the carnage, but then “I did a stupid thing,” he says, allowing Simpson to write the story. The reason why this was a mistake is because “John didn’t know, at that stage, a great deal about the politics of Lebanon” – but I also suspect some professional rivalry, a suspicion later reinforced when Christopher gripes that his role in obtaining the scoop has been obscured. “I’m written out of that, I’m not even mentioned by Simpson in his book. Which I was quite annoyed about – so I’m going to put the record straight, in the one I’m doing”. He pauses thoughtfully. “But that’s the way it goes. I mean, I could be accused of the same thing. It’s a parade of egos, in a way, in television. There’s a lot of competition.”

He and Simpson (now perhaps the best-known BBC reporter) filmed the carnage, but then “I did a stupid thing,” he says, allowing Simpson to write the story. The reason why this was a mistake is because “John didn’t know, at that stage, a great deal about the politics of Lebanon” – but I also suspect some professional rivalry, a suspicion later reinforced when Christopher gripes that his role in obtaining the scoop has been obscured. “I’m written out of that, I’m not even mentioned by Simpson in his book. Which I was quite annoyed about – so I’m going to put the record straight, in the one I’m doing”. He pauses thoughtfully. “But that’s the way it goes. I mean, I could be accused of the same thing. It’s a parade of egos, in a way, in television. There’s a lot of competition.”

There’s a slight contradiction in Father Panaretos. On the one hand, he studied psychology, the science of understanding people; his personal style is humble, serene, approachable, very friendly. On the other hand, he keeps a certain distance. His hobbies are mostly solitary, reading non-fiction (currently Life Without Limits by Nick Vujicic, the bestselling memoir of a man who was born without limbs) and being in Nature. “I like somewhere quiet,” he tells me, “this is why I loved the monasteries. I like socialising with people but I’m very, very careful. Because people are a bit selfish sometimes, they’ll take advantage of you.” His credo, he says, is “Be friends, but with boundaries… You cannot have people just taking and taking. They’ll take, and then they leave you empty.”

There’s a slight contradiction in Father Panaretos. On the one hand, he studied psychology, the science of understanding people; his personal style is humble, serene, approachable, very friendly. On the other hand, he keeps a certain distance. His hobbies are mostly solitary, reading non-fiction (currently Life Without Limits by Nick Vujicic, the bestselling memoir of a man who was born without limbs) and being in Nature. “I like somewhere quiet,” he tells me, “this is why I loved the monasteries. I like socialising with people but I’m very, very careful. Because people are a bit selfish sometimes, they’ll take advantage of you.” His credo, he says, is “Be friends, but with boundaries… You cannot have people just taking and taking. They’ll take, and then they leave you empty.” That’s a whole other question, of course: how has this transplanted African found life in Cyprus? It took some getting used to, he admits. Kenya is “more social than here”, presumably a nice way of saying that we’re more uptight; strangers greet you in the street in Nairobi, kids play outside – as he and his siblings once did – without waiting for their parents to organise play dates. Initially he found it slightly boring on our little island – but then “I said to myself: ‘If you want to survive in Cyprus, if you want to enjoy life in Cyprus, start liking whatever is there’.” (He’s now developed a taste for local music, citing Giorgos Kalogirou as a favourite.) On the plus side, he’s never encountered any racism – even when people don’t know he’s a priest, which they often don’t. “People get confused,” he says wryly; at least some of his fellow students – and a few professors – have assumed that his black cassock must be some kind of traditional African costume.

That’s a whole other question, of course: how has this transplanted African found life in Cyprus? It took some getting used to, he admits. Kenya is “more social than here”, presumably a nice way of saying that we’re more uptight; strangers greet you in the street in Nairobi, kids play outside – as he and his siblings once did – without waiting for their parents to organise play dates. Initially he found it slightly boring on our little island – but then “I said to myself: ‘If you want to survive in Cyprus, if you want to enjoy life in Cyprus, start liking whatever is there’.” (He’s now developed a taste for local music, citing Giorgos Kalogirou as a favourite.) On the plus side, he’s never encountered any racism – even when people don’t know he’s a priest, which they often don’t. “People get confused,” he says wryly; at least some of his fellow students – and a few professors – have assumed that his black cassock must be some kind of traditional African costume.

This, I suspect, is the bottom line: Helen Christofi’s life – and the life she represents, this new way of life ushered in by the 21st century – is simultaneously narrower and broader than most people’s. Her world is the small Nicosia flat with the PC in the living room, but her world is also the entire planet, reflected in the likes of 4chan and the multi-player games where you always seem to get “some Russian guy screaming at you”. What she’s missing is the bit in between, the actual – but limited – world of the physical society around her.

This, I suspect, is the bottom line: Helen Christofi’s life – and the life she represents, this new way of life ushered in by the 21st century – is simultaneously narrower and broader than most people’s. Her world is the small Nicosia flat with the PC in the living room, but her world is also the entire planet, reflected in the likes of 4chan and the multi-player games where you always seem to get “some Russian guy screaming at you”. What she’s missing is the bit in between, the actual – but limited – world of the physical society around her.

He works hard; according to the Internet Movie Database he made seven films in 2018, two already in 2019, and has eight more awaiting completion. Why so many? “Because they all were good,” he replies implacably. I assume it also fits his lifestyle – he lives alone, in Palm Springs, in a former library designed by Swiss-born architect Albert Frey; he’s never married, or wanted children – and also speaks to some inner need for being seen. “I liked the attention,” he tells me earlier, speaking of his instant celebrity in the 60s – and it’s true, he does. Despite his rarefied manner, he seems to get a kick out of being recognised in public, and may even try to provoke it. “I was shooting a movie in Brisbane,” he tells our waitress apropos of nothing, hawking his movie-star status; “I didn’t recognise you before,” she admits apologetically when she returns with our drinks (it’s unclear if she recognises him now, or is just acknowledging the air he exudes of a person one ought to recognise). Later, he startles some random stranger who sits down next to us by breaking off to greet him cordially; the stranger just stares in bewilderment, clearly more of a Game of Thrones fan.

He works hard; according to the Internet Movie Database he made seven films in 2018, two already in 2019, and has eight more awaiting completion. Why so many? “Because they all were good,” he replies implacably. I assume it also fits his lifestyle – he lives alone, in Palm Springs, in a former library designed by Swiss-born architect Albert Frey; he’s never married, or wanted children – and also speaks to some inner need for being seen. “I liked the attention,” he tells me earlier, speaking of his instant celebrity in the 60s – and it’s true, he does. Despite his rarefied manner, he seems to get a kick out of being recognised in public, and may even try to provoke it. “I was shooting a movie in Brisbane,” he tells our waitress apropos of nothing, hawking his movie-star status; “I didn’t recognise you before,” she admits apologetically when she returns with our drinks (it’s unclear if she recognises him now, or is just acknowledging the air he exudes of a person one ought to recognise). Later, he startles some random stranger who sits down next to us by breaking off to greet him cordially; the stranger just stares in bewilderment, clearly more of a Game of Thrones fan.