When the people of Britain go to the polls on Thursday there is a Greek Cypriot among those hoping to end up in the House of Commons. NADIA SAWYER meets him

With the UK General Election being held on Thursday all eyes from Cyprus should really be focussing on just one London seat, that of Islington South & Finsbury where two contenders have connections to Cyprus.

One is the Labour candidate and Shadow Foreign Secretary Emily Thornberry. A close ally of Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, who is contesting the Islington North seat, she is considered by some of her political antagonists to be a ‘champagne socialist’ and has been ridiculed by the British press for her television interview gaffes. Her father, the late Cedric Thornberry was, in his own words, “Deputy Special Representative of the Secretary-General in Cyprus participating in the inter-communal negotiations, UN member of the Greek-Turkish Committee on Missing Persons and Political Adviser to Unficyp (1981-2)”, and, by the late 1990s enjoyed semi-retirement in Pano Pachna, near Limassol. Ms Thornberry has herself visited Cyprus, including the north, and has promised her political support but, according to the official record of parliamentary proceedings, has never once, neither in 12 years of being an MP nor as Shadow Foreign Secretary, mentioned the island in the chamber of the House of Commons.

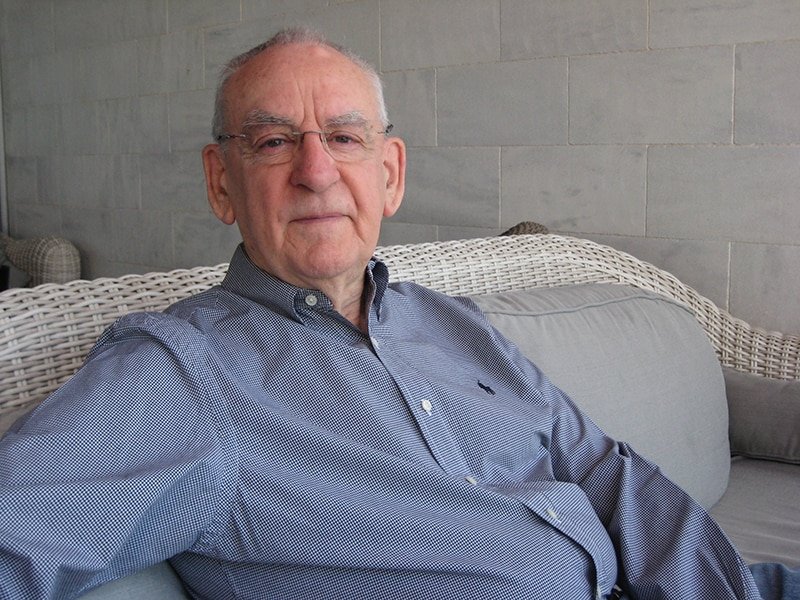

Her Conservative opponent, on the other hand, is promising to refer to Cyprus in his maiden speech should he win. Indeed, if elected, Jason Charalambous would be the first ever British MP with full Greek-Cypriot heritage. His father, George, was born in Pano Arodes but spent his early childhood years in Polis and his mother, Anastasia, was raised in Aglantzia, her family originating from Karmi, near Kyrenia. “They came to the UK as children of economic migrants,” says Jason during a Skype call interrupting his campaigning.

His father’s father served in the Cyprus Regiment of the British army in Egypt during World War II, and worked as a blacksmith in Cyprus, later transferring the skill to a job in the UK. His mother’s father had been a barber and a builder who also put his trades to good use in his adoptive country. Charalambous’ two Cypriot grandfathers settled their families in north London, enrolling their children in local schools. After obtaining his ALevels, George wanted to go to university but “he couldn’t afford it,” says Jason, “in fact, he couldn’t even afford a bus pass”. Working various jobs in the rag trade, George eventually set up his own factory and, with the help of family and friends, developed a successful business manufacturing women’s clothes. Meanwhile, Jason’s mother Anastasia had been to the London College of Fashion and was working as a fashion designer when she met George. Their engagement in July 1974, on the night of the Turkish invasion, was a memorable one.

“Everyone was glued to the television when they were meant to be celebrating”, recounts Jason. There followed three children, with Jason the last-born – in Enfield in 1986.

In addition to running the factory together, where Jason fondly remembers being “on the cutting room floor”, his parents opened a shop in Islington, working seven days a week. When the clothing manufacturing industry in London collapsed due to overseas competition, they switched to selling clothes wholesale from another shop. His parents’ hard work ethic would serve as the inspirational backbone to Jason’s life.

While his parents were toiling, Jason and his siblings were studying, even going to Greek school on Saturday afternoons and Monday evenings, which proved very useful when visiting relatives in Cyprus. He produces a photo of himself as a fair-haired toddler in the village of Pano Arodes, surrounded by his father’s family. “I vividly remember being in that village as a child and having a real bond with my great aunts,” he reminisces. “It was remote, traditional, poor… but I had a great time there, on the donkeys, getting lost in the fields…”.

Subsequent family holidays were taken all over Cyprus, staying with relatives in the major towns. “From a young age, I had a good understanding of the island and the people,” he says, now a proficient Greek speaker. Although his teenage passion was architecture, an interest that was to later manifest itself in an important cause, he planned to study modern history at university, but was persuaded by his father and brother to do law. A graduate of King’s College, London, Jason went on to the Inns of Court School of Law to do a two-year, evening vocational course while working during the day. He was called to the Bar in 2009 and then cross-qualified as a solicitor qualified to practice as a solicitor-advocate, a position he currently holds both with a city law firm specialising in commercial and maritime law and a high-street law firm that he co-partners with his brother.

Nothing so far in Jason’s upbringing indicates that he would get into politics, so what ignited his interest? “When I was at primary school, Conservative MP Michael Portillo came and spoke. I thought that this was someone who was really inspiring”. The following year Labour MP Stephen Twigg gave the school a tour of the Commons and Jason was the only pupil able to identify Winston Churchill’s statue. “That, I think, was what planted the seed,” he says. In later years, there was a chance encounter with the former Conservative Party leader William Hague on a geography field trip and after the General Election of 2005 Jason decided to join the party. At university, he got his first taste for public speaking when an amusing speech saw him elected as president of his student hall. After university he competed in the party’s debating tournament, winning the final round at Westminster.

Responsible for the youth branch of the party in the London boroughs of Barnet, Enfield, Haringey, Camden and Islington, Jason inspired young people to get involved, by hosting social and political events. It was at a local party event, hosted by Theresa Villiers, former Northern Ireland Secretary, that he found himself sitting next to the current Prime Minister Theresa May when she was Home Secretary. “She didn’t strike me as a typical politician,” he says. “She struck me as someone with gravitas, depth of character and a reassuring seriousness, yet charming”.

It is this initial meeting that sticks in Jason’s mind and convinces him that she is the best person to lead the UK through the Brexit process. “The country voted in a democratic referendum to leave the EU… that was the will of the majority and that must be respected. I believe that if you start to undermine democratic processes then we are in trouble, because democracy underpins the very fabric of society”.

When he talks about democracy so passionately, it is easy to believe there is Greek blood flowing through his veins. When it comes to negotiating with the EU, Jason is also determined that May should be standing on the crease. “You need someone who is strong, who can bat for Britain and win,” he says. Coincidentally, like May Jason was a ‘remain’ voter. “I have since reminded myself that the EU while it started with noble intentions now appears to be heading in a different direction”. He cites the example of the EU-driven appropriation of bank deposits in Cyprus in 2013 as an illustration of this.

As Cyprus recovered from its financial crisis, the still single Jason gives credit to the advice and support the British government gave to its Cypriot counterpart when it came to public sector reform. Citing another symbol of the important relationship between the two countries, Jason refers to their co-operation on defence issues and the respective visits of defence ministers within the last year. In fact, he sees an improvement in Anglo-Cypriot relations, which he trusts, “will continue post Brexit”. Continuing along the same theme, he also understands the concerns of British nationals living in Cyprus.

“I know how important it is for them to live their lives with security and certainty,” he says, hoping that

British citizens, wherever they reside in the EU, will be granted the right to remain in those countries.

Currently a Conservative councillor for Cockfosters in the borough of Enfield, an area containing one of the largest percentage of Cypriots in the UK, he is part of a racial equality effort attempting to bridge the gaps between migrant and host communities. When a neglected mansion in Enfield caught his architectural eye and he learnt about its historic, World War II intelligence-gathering role, he founded (after three years of hard campaigning) and now chairs, the Trent Park Museum Trust. The Trust is a charity working on the establishment of a museum and learning centre and is endorsed by among others another local boy, Sir David Jason (of Only Fools and Horses fame). Jason is also a governor at his former primary school and a fundraiser for an Islington-based disabled children’s charity.

Maiden speeches in the Commons are often memorable, but with so much to talk about, would Jason mention Cyprus if he were elected? “Yes, I would refer to Cyprus in the context of unresolved conflicts and refugees,” he confirms, believing that solving the Cyprus problem could be the catalyst for resolving other international issues. He would explain that in 1974 over 200,000 people were displaced on the island. He would argue that “every refugee should have the right to return to their home”. It saddens him that some Cypriot refugees in London still carry the keys of their Cyprus houses in their pockets. “You are reminded that, no matter how long the passage of time, only a person who has experienced being uprooted from their home can truly understand that pain”.

Indeed, Cyprus and its people have never been far from Jason’s mind. Since 2015 he has been Chairman of the Conservative Friends of Cyprus (CFC). One of his first achievements in the role was arranging for Philip Hammond, Foreign Secretary at the time, to speak to the Cypriot community. “He knew the details and issues better than anyone in the room,” Jason recalls. In 2016, Jason hosted his second CFC event at the Conservative Party Conference, where Boris Johnson, who succeeded Hammond, spoke of his desire to see a solution to the Cyprus issue. “This level of engagement is invaluable,” says Jason, adding that one of the goals of the CFC is to get the Cypriot community more involved in politics. “Our community is under-represented. We have never had an MP in UK parliament and we are a community of 300,000 persons, it is only right that British Cypriots play a more active role in British political life”.

Indeed, Jason has himself led two parliamentary delegations to Cyprus, in 2015 and 2016, showing British MPs the Cyprus problem first hand and meeting with UN and political representatives on both sides of the island.

Jason’s passion for Cyprus is demonstrated not just with words and deeds, but also with pictures – behind his desk maps and prints of the island are clearly visible. A son of immigrants who is proud not only of his British identity but also of his Cypriot heritage. For his endeavours alone, one feels compelled to persuade friends and relatives in Islington South & Finsbury to vote for him, especially since he is almost half the age of Thornberry and contesting one of Labour’s safest seats. Not for the Conservative party, not for Brexit, but for Jason – just because he is a champion for the Cypriot community and a force to be reckoned with.

The post A champion for the Cyprus community appeared first on Cyprus Mail.